With a monsoonal climate, nearly all rain falls in the wet season (average ~800mm/year). Waterbodies including dams, water holes, and wetlands, soil water, and groundwater including river bedsands fill up in the wet and need to meet water needs through the dry. River flows to the Gulf also play an important role in supporting the estuary - it’s important for available water to be shared.

Streamflow is measured using stream gauges. Surface water can be seen in satellite imagery. Groundwater levels and quality are measured using monitoring bores.

Streamflow at stream gauges can also be predicted using catchment models. Catchment models capture the relationship between weather data and stream-gauge data, as well as accounting for the time it takes for water to flow down the river.

At finer scales (e.g. 0.05°, ~5.5km), distributed hydrological models can provide an estimate of past and future water budgets, showing how rain is partitioned between evapotranspiration, infiltration, runoff, and changes in stored water in the landscape.

There are currently no groundwater models for this region. A groundwater model would represent flow and changes in water levels within aquifers and bedsands.

Access to water

Water can be accessed from:

- Rivers, streams - pumping water while they are flowing

- Bedsands and aquifers - pumping water, or digging holes in the sand

- Soil - enhancing infiltration and soil water retention

- Waterbodies - capturing overland flow or storing water, especially in farm dams

The Gulf Water Plan regulates taking water from watercourses, overland flow, bedsands, and some aquifers. Taking water from the Great Artesian Basin aquifers is regulated by the Great Artesian Basin and Other Regional Aquifers (GABORA) plan. In general, a water license is needed to take water, and a development application is required to build infrastructure that diverts or stores water, e.g., farm dams, pumps, and channels.

Taking limited volumes of water for stock and domestic use typically does not require a license, but may still require filling out a notification form.

Agriculture

Volumes of water needed for irrigation are typically much larger (e.g. 2-10 ML/ha/year). During the dry, rivers and streams are not flowing. Consolidated sandstone aquifers in the region typically have low flow rates (~1-3 L/s), with water needing to be pumped into storages to be used. Bedsands have a limited storage capacity but depending on the location are able to meet irrigation needs for the whole season. High evaporation and sandy soils mean that losses from farm dams and storages tend to be high, but they can still be useful.

Existing high value horticultural crops, especially mangos, are irrigated using drip irrigation with water licenses allowing taking of water from the bedsands. Water is generally of good quality, but with high iron content, which can cause blockages in drip irrigation systems. Increasing the current limit on pumping from bedsands would only be possible with a better understanding of flows into and out of different pools in the bedsands. In some places, bedsands bores do go dry and depth to water has been increasing, suggesting that there are places that water extraction may already be at its limit.

Weather conditions for agriculture are typically good enough that dryland crops can grow well in the region. Managing soil water is important because intense rainfall tends to runoff rather than infiltrate, and coarse deep sands do not hold water well. Some areas do have better soil water properties, and it has been found that a number of crops tend to grow deeper than usual roots that allow plants to access water deeper in soil and from the bedsands themselves. This includes leucaena, which is grown for cattle to feed on. Managing groundcover and landscaping works can also help improve infiltration and soil properties. Within cleared areas, no specific licenses or approvals are required for most soil management activities.

Weather conditions are still sufficiently variable that crops may fail due to lack of water during establishment or late in the season, especially if there are long periods of time without rain at the start or end of the wet. Reliability of dryland cropping could therefore be improved with targetted use of irrigation. The river is often flowing early in the wet due to rain upstream, even if it has not rained locally. TODO could analyse this. Relatively small dams and limited “emergency” use of water from bedsands could also save crops that would otherwise fail. The volumes of water needed and costs involved have not yet been analysed. There is also currently no specific support for temporary water licences or sharing of required irrigation equipment, though bedsands licences can technically be traded between properties within zones.

Plans suggest that the proposed Green Hills dam could provide 90 and 40 GL of water with 95% monthly reliability delivered between February and December and 85% monthly reliability delivered between February and May, respectively. The Detailed Business Case in 2020 suggested building concrete channels and buffer reservoirs on the north-side of the river to deliver water. It has also been suggested that water could instead be released into the bedsands, or that channel infrastructure could run north of the Gulf Development Road, further from the river. Leasehold land would likely need to be resumed and development of the dam would likely involve a major and widespread shift from grazing to intensive irrigated agriculture for the dam to be financially viable. The Detailed Business Case estimated that the planned dam would cost $887.2 million, with 77% of funding suggested as being sourced from the government (QLD and Australian), and provide a cost-benefit ratio of 1.15. The next step for planning of the dam would be an Environmental Impact Statement. There is currently no plan to commission the Environmental Impact Statement, and no specific promises of funding for the dam. There is a range of interest from local landholders, with some already involved in intensive irrigated agriculture, some committed to grazing enterprises, and others not interested in starting something new at their stage of life.

New large farm dams for irrigation purposes appear to be possible at a range of locations within the catchment, potentially with capacities up to 8GL for some gully dams. New farm dams can only be built where vegetation is already cleared and require a licence for overland flow water. The Etheridge Agricultural Precinct project is looking to streamline approval processes.

It also appears that current water storage in the region is underutilised, i.e. there are existing large farm dams and old mining dams that are currently used only for watering stock and domestic uses, and which hold enough water to be useful for irrigation. Currently, these dams may also be increasing the volume of water lost to evaporation rather than recharging the bedsands or flowing to the Gulf. The bedsands have an estimated volume of 17- 20 GL1, a similar volume to the largest in-stream dam in the region (Copperfield River Dam at 20 GL2). Therefore, once smaller on farm dams are included, there is already substantial water storage in the catchment that could be partially or majority reallocated for irrigated agriculture, with groundwater from bores with too low yield for support irrigation being used to make up the supply to current stock and domestic users. Also, new surface water stores have been recently constructed with the sole purpose of town water supply (e.g., Charleston Dam3,4,5). In principle, releasing water from these existing dams could recharge pools within the bedsands and allow greater pumping. Construction of targeted pipelines or water carting could also deliver water in some cases. New infrastructure would require development approvals, but use of existing dams is otherwise not currently regulated TODO confirm. However, these dams are usually not located on the same property as existing agricultural or cleared land. Potential infrastructure required and applicable regulations have not yet been studied. Formal arrangements at a fair price would likely be required between dam owners and water users in a context where irrigators are counting on access to that water.

While the proposed Green Hills dam would represent a step change in the size of irrigated agriculture in the region, improved soil water management and use of existing and potential new dams already provide a clear pathway for gradual expansion of agriculture, but require further research on potential for targetted, often flexible infrastructure and supporting business and regulatory arrangements.

Potential impacts of water use

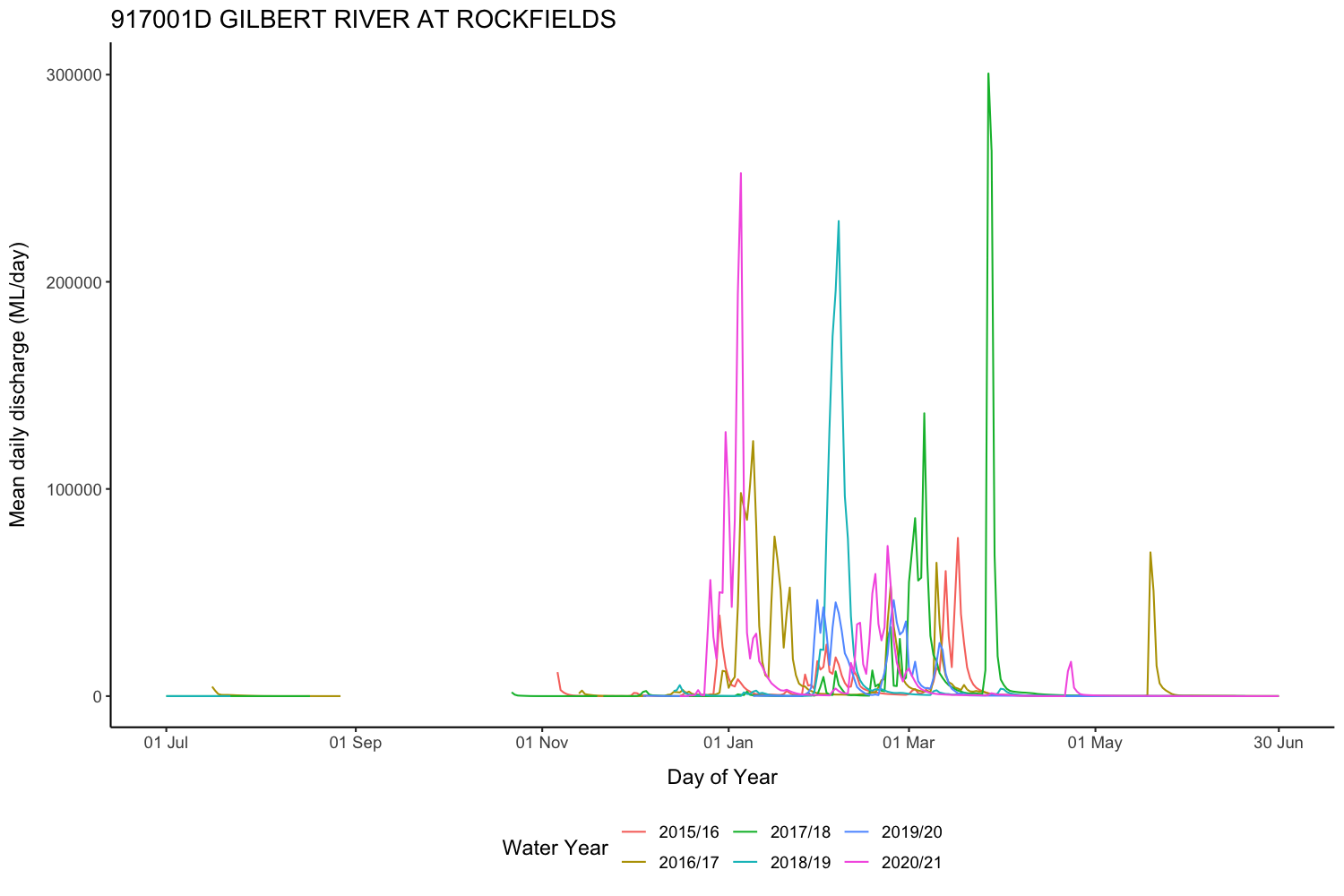

Changing the use of water always has an impact, as it changes the water budget of a region. Increase in water use in the GRAP, particularly for the large volumes used in irrigated agriculture, would change the flow patterns of the Gilbert River (and potentially some tributaries), including flood flows and low flows.

Flood flows are likely to be decreased by dams and pumping, but flooding may also be impacted by changes in land use and changes to vegetation and location of waterholes within the river. There are also links to erosion. Flood flows are important for end of system flows into the Gulf.

Changes in low flows may include shorter periods of time that rivers are flowing, waterholes have water in them, and water levels within the bedsands are closer to the surface. Deeper water levels within the bedsands may be reached, and pools in the bedsands may become disconnected. Depth of water in the bedsands could impact on existing stock and domestic water users, existing cropping where plants are accessing bedsands, as well as ecosystems dependent on water in bedsands.

The Gulf Water Plan is the primary regulatory instrument to anticipate and manage potential impacts on other water users and the environment.

Increases in water use are also likely to come with other changes, e.g. on workforce pressures, demographics, demand for housing and services, and distribution of weeds and pests. Some of these impacts may be within the scope of formal impact assessment processes required for large projects. A comprehensive list of potential impacts does not yet exist, however, the detailed buisness case for the proposed Green Hills dam does begin to highlight secondary changes from water development and agriculture expansion in the region.

Resources

On this website:

Footnotes

- Department of Natural Resources (1998) Gulf Region Study: Gilbert River Bed Sand Investigation Exploratory Drilling Programme

- Agricultural resource assessment for the Gilbert catchment (Petheram et al., 2013)

- Etheridge Shire Council Charleston Dam info page

- Charleston Dam Facility

- Detailed Design of the Charleston Dam